In honour of International Women’s Day, four VCHRI researchers share their experiences and offer advice for the next generation of women in science.

Every year on March 8, we take time to recognize International Women’s Day, a global event dedicated to celebrating the achievements of women around the world and raising awareness for gender equality.

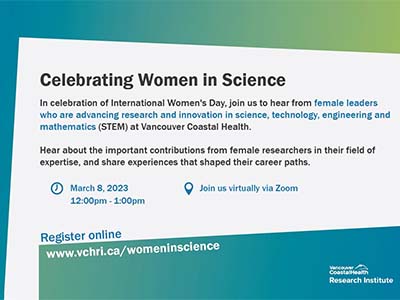

To celebrate International Women’s Day this year, we are hosting an online event with female scientists at Vancouver Coastal Health who are making waves in the research community. Leading up to the special event, these four inspiring researchers answer some questions about their journeys in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) and share advice for other aspiring scientists:

Do you have any female role models that inspired your career path? How did they help encourage you to pursue health research?

Mehwish: Growing up in a community where there are pre-defined gender roles, I did not have many examples of women in STEM, but I was fortunate to have a family that supported my education. I also had female science teachers who encouraged me to pursue my interests in biology and chemistry. In college, I was drawn to health research because of the potential to make a real impact on people's lives. Later, I was awarded the prestigious Marie Curie PhD fellowship that proved to be instrumental in my career as a researcher in neuroscience. My PhD supervisor, Dr. Asla Pitkanen, and my postdoctoral mentor, Dr. Cheryl Wellington, are both very successful women in the neurotrauma field which motivates me to continue to make an impact as a woman of color in STEM.

Katlyn: I was always fascinated by science as a child, but my love of research was born in undergrad through the leadership of two female professors. Working with them inspired a passion for problem-solving and creative thinking to help answer complex health problems. Now pursuing my graduate studies, I am keen to explore opportunities that support young women and girls in science through various initiatives. I hope this will allow them to envision themselves in STEM and spark their own curiosity for scientific discovery.

Lyndia: My postdoctoral supervisor, Dr. Ada Poon, helped me during my transition from a graduate student to a faculty member. Her group develops novel integrated electronics systems for biomedical applications, such as wireless devices for optogenetics. Her research excites and inspires me, and she has also given me practical advice on how to navigate academia as a female engineering faculty member. I cannot thank her enough for her guidance and support.

Amina: My journey in STEM started with my grandmother as a role model, who taught me that the sky is the limit. She was an independent and inspiring woman during an era where Arab and Muslim women did not have a voice. Many other women also had a lasting impression on my career. My PhD supervisor was one of the few women researchers who studied prostate cancer 40 years ago. She introduced me to the field of prostate cancer and its community and encouraged me throughout every step of my career.

Why do you think it is important for women to be represented in STEM? What unique perspectives do you bring to health research as a female scientist?

Mehwish: Women make up half of the global population, so it is important that our perspectives and experiences are represented across all fields. In health research, having a diverse range of perspectives is especially important because different groups may experience different health outcomes or respond differently to treatments. Additionally, by encouraging and supporting girls to pursue careers in STEM, we can address the gender gap and provide more opportunities for future generations of women in science.

Katlyn: Even in 2023, the under-representation of women persists in STEM fields — and especially in leadership positions. Although I continue to see progress being made toward gender parity, this progress is slower at higher levels of education and leadership. Finding creative and sustainable solutions to the world’s complex problems requires representation and varied perspectives at all levels.

Lyndia: As research and technology development become increasingly multidisciplinary, we will benefit from diverse expertise and perspectives. Increased representation of women in STEM will help give confidence to girls so they can succeed in these fields. Specifically in health research, my work now is starting to focus on sex- and gender-based differences in a traditionally male-dominant field of injury biomechanics. My current role empowers me to direct research to fill the gaps in the collection of women’s data and investigation of injury risk factors in women.

Amina: Female representation is crucial to advancement in STEM because it increases diversity of perspective. Women tend to be more open to the opinions of others, which leads to more robust decisions and outcomes. I am not only a female scientist, but am also a tri-lingual, Arab, Muslim North African Canadian. I hope my unique perspective can break down barriers and pave the way for female minorities.

What are some unexpected challenges you have faced being a woman in STEM, and how did you overcome these challenges?

Mehwish: There is a perception that women are not as capable or committed to their careers as men are. Because of this, I have had to work harder to prove myself and demonstrate my expertise and I have also had to navigate subtle forms of sexism. However, I have found that having a supportive network of colleagues and mentors has been crucial in overcoming these challenges. It is so important to speak up and advocate for yourself when you encounter discrimination.

Katlyn: While I have had the privilege of living in a time and place where I have been relatively free to pursue my career of choice, there are still obstacles that discouraged me from doing so — the largest being reconciling society’s stereotypes of what it means to be a woman and what it means to be a scientist. It has been hard to find where I fit into these reductive views. Luckily, I have found solace in surrounding myself with other women in the field who are experiencing the same challenges.

Lyndia: It is difficult enough being a woman in today’s society, and even more challenging to be a woman in STEM. We are often juggling many roles and responsibilities. I myself have recently become a new mother over the past year, and balancing this role with my career has been a tremendous challenge. I am not sure that I have entirely overcome the challenge, but I am feeling better and more confident day-by-day that I can handle both of these important jobs simultaneously. Thankfully, my family has been supportive and I have learned to seek help when I need it.

Amina: Over the years, I have faced several gender biases and stereotypes. Being an assertive woman is often negatively viewed as overly aggressive, while being an assertive man is positively viewed as being a leader. Additionally, having a non-English accent can lead others to underestimate me. To overcome these complex challenges, I put all my efforts into my research program and take any opportunity to contribute to my community. I continually broaden my academic interests and regularly reach out to my network of inspiring women for help and support. They are my cheerleaders.

What advice do you think women and girls should know about working in health research?

Mehwish: Never let anyone tell you that you cannot do something because of your gender. There are still barriers to overcome, but the field of health research needs more women and girls who are passionate about making a difference. Find mentors who can support and guide you, and seek out opportunities to gain experience and build your skills.

Katlyn: A key quality for women in health research to have is perseverance. Your experiments will undoubtedly fail, and likely many times. You need to have perseverance in order to push through those difficult situations.

Lyndia: You need to take good care of yourself before you can help others, so it is important to prioritize your own health and happiness. When you are in a situation where imposter syndrome kicks in, step back and keep in mind that the problem may not be on your end. Absorb any constructive feedback, but distance yourself from those that consistently make you feel undervalued.

Amina: Believe in yourself and your intellectual abilities, recognize your strengths and admit your weaknesses. Success in health research is hard work — the path is long but the intellectual rewards are great, so it is crucial to celebrate every achievement, no matter how small.

How do you think we can break down barriers to encourage people of all genders to pursue careers in STEM?

Mehwish: Overcoming barriers in STEM requires both individual and systemic efforts. It starts with creating a more inclusive and welcoming culture by working to eliminate discrimination, providing mentorship opportunities and promoting diverse experiences. We also need to make STEM education and careers accessible to a wider range of people, including those from low-income backgrounds, under-resourced schools and marginalized groups. In the meantime, we need to celebrate and highlight the achievements of women and other under-represented groups in STEM to inspire future generations.

Katlyn: Institutionally, there needs to be equal representation at all levels. One of the reasons women may not pursue academia is because of the dated expectations that one cannot juggle work and family life. Further, academia can be a rather thankless job, so it is important for scientists of all genders to be appreciated and rewarded for their hard work and success — both in pay and in recognition.

Lyndia: Systemic barriers have been established over a long period of time, but we can start breaking them down by making changes one step at a time. If each of us can make a small effort, such as talking to a young female student, including a module in our regular teaching to highlight the lack of gender diversity in STEM or speaking up in a hiring discussion, these changes will accumulate and amplify. We also have the opportunity to help promote EDI in research, so I encourage everyone to identify gaps in sex- and gender-based investigations in their field. By committing to this work, I am hopeful that we will continue to make meaningful progress.

Amina: Commitment to Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) initiatives by government and university institutions is changing the landscape, but there is still a lot of work to do. Some attribute the successes of minorities and women to EDI commitments rather than their actual achievements, which is harmful as it undermines the importance of EDI and minimizes the hard work of minorities and women. Going forward, we need to increase mentorship opportunities, address discrimination in STEM and address the pay gap.